Poster

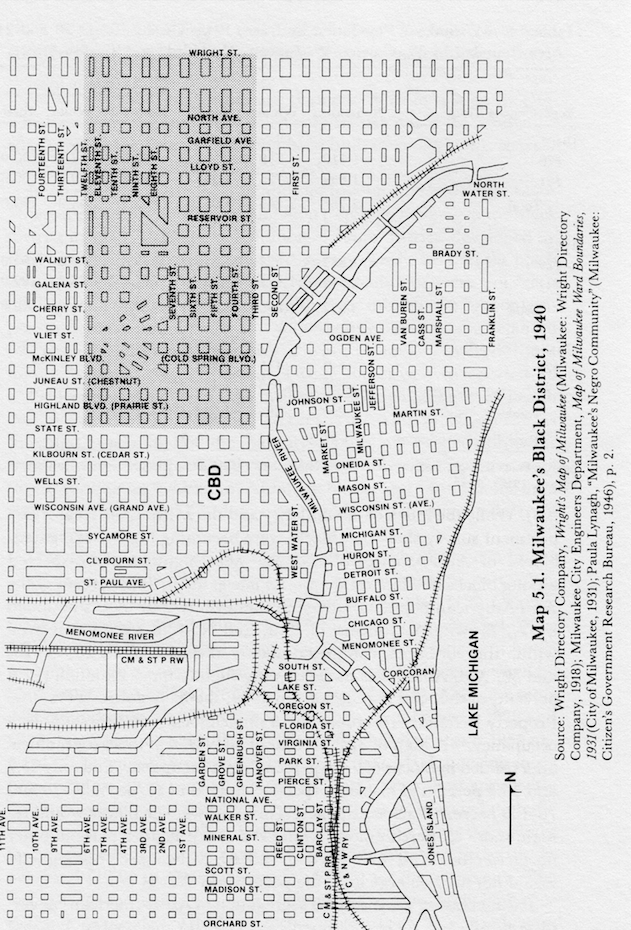

Bronzeville and Environs, 1940

Timeline

1910 | There are fewer than 1,000 African Americans in Milwaukee. Few, if any, are in the industrial workforce.

|

1930 | A cluster of black-owned businesses, serving a black clientele, emerges around Seventh and Walnut.

|

1937 | Congress passes the United States Housing Act of 1937.

The federal government builds Parklawn, one of Milwaukee's first public housing projects, north of Capitol Drive.

|

1940 | The city's African American population reaches 8,800.

|

1941 | Franklin Roosevelt signs Executive Order 8802, banning discrimination in all work governed by federal defense contracts.

|

1944 | The Milwaukee Health Department surveys housing conditions in 43 square blocks bounded by North Fifth, North Ninth and West Vliet Streets, and North Avenue. About half the dwellings are found to be substandard (although many could be rehabilitated at low cost). The survey finds that the population is disproportionately made up of low-income blacks who can't afford to meet the rent required by (largely absentee) owners to maintain the properties in good condition.

The Federal Public Housing Authority approves a war housing project for Milwaukee, which eventually becomes Hillside Terrace.

Mayor John Bohm creates the City of Milwaukee Commission on Human Relations.

|

1942 | A federal agency (FEPC) orders five Milwaukee manufacturing companies to cease and desist from discriminatory hiring practices.

|

1946 | The Citizens' Governmental Research Bureau issues a report entitled “Milwaukee's Negro Community.”

|

1949 | Congress passes the United States Housing Act, Title I, providing federal aid to cities for slum clearance and blight elimination. The act requires participants to provide both temporary and permanent housing for persons displaced by federally funded projects.

|

1950 | The census sets the African American population of Milwaukee at 21,800. The city finishes the Hillside Terrace housing project. A total of 208 individuals (61 families plus 22 lodgers) were displaced by the project; their average rent was $15.92 per month. Hillside Terrace had 232 dwelling units (the development now has a total of 421 units). According to a report prepared by the city in 1946, the average rent was expected to be $24.59 per month.

Wartime state and federal rent controls expire.

Mayor Frank Zeidler writes a blistering letter to the Milwaukee County Property Owners Association, accusing its leadership of "an anti-labor attitude, an opposition to community redevelopment, a tendency to create division and ill-will between tenants and landlords, and ... support for profiteering and inflation."

|

1951 | Two referenda are placed on the ballot. Voters say "yes" to slum removal and "no" to public housing. A court challenge follows.

|

1952 | The Sixth Ward Better Housing League (Josephine Prasser, corresponding secretary) submits a petition to the Common Council with 1,300 signatures asking for slum clearance and better housing. The council places the petition on file. In a follow-up letter, Prasser writes "It is high time that we stop pointing at the Negro as an outsider. ... All he needs is the same ENVIRONMENT, the same EDUCATION and TRAINING and the same OPPORTUNITY as others" (capitalized in original).

The Mayor's Commission on Human Rights issues a report which states that "Segregation of Negroes (and other easily identifiable minority groups) in housing is more widely and openly practiced in Milwaukee than other fields of overt prejudice. [It] has resulted in a ghetto pattern which is one of the most obvious defects in the city's outward appearance. A qualified Negro will find it easier to acquire an education, to secure medical attention or hospitalization, to obtain a decent job at fair wages, than to secure housing accommodations in Milwaukee, even though he be educated, cultured and financially responsible. ... The poorest immigrant who comes to Milwaukee and who pulls himself up the economic and social ladder by his own efforts can move into whatever residential neighborhood his pocketbook permits or his wishes dictate. But a Negro, regardless of his financial or educational status, finds it almost impossible to move out of the worst housing in this city. This pattern of relegating Negroes to a ghetto is Milwaukee's most shameful violation of the American creed that all men are created equal."

Rozilia Merrill of 2338 N. 6th St., writes the following to Mayor Zeidler: "We are a family of three, husband, wife and 14-year-old boy ... sharing a small cottage with another family. On March 8, 1952, notice was served us to move by April 9, 1952. We don't know the reason, but believe higher rent is wanted by owners. However, from March 9, 1952 to the present date (March 23) we have been seeking an apartment only to be turned away with 'We aren't interested in renting to colored' or 'It's already rented.' And in many cases the ad continues to be run in the papers. We all know that every person is a human being and is entitled to be treated as one. We don't want to live where we aren't wanted nor rent from anyone who refuses to rent from us, but we must live somewhere and someplace. Mr. Mayor, my husband works every day, we pay our bills and have the very best credit references. Our word need not be accepted, it can be proven. My son isn't the brightest high school student, but we don't have any trouble with him otherwise. My husband has been employed steadily for 4 years, at International Harvester. His salary nets $63.45 weekly and we would be proud of any information you would obtain thru investigation of our family. We only want a chance to live in a good house, neighborhood and among good neighbors. ... I realize you are a busy man, but please refer this matter to someone who will help us!

|

1953 | The City Health Department ramps up inspections in an area bounded by North Third, North Seventh, West State and West Galena Streets. Inspectors issue rehabilitation orders for 131 of the 204 structures (64%). Many of the buildings are repaired; a few are abandoned or condemned, and razed. However, the inspection does not include sheds and outbuildings. In the same year, building inspectors surveyed the area bounded by North Sixth and Seventh Streets, and and West Walnut and West Galena Streets (the Hillside Neighborhood Redevelopment Project). They found that the area's 64 original lots had been subdivided into 121 parcels containing 159 buildings with little or no open space; 88% of the buildings were in "less than fair" physical condition and 71% did not have the minimum sanitary fixtures required by code. A letter writer, Rudolph Lang, who frequents the Sixth Ward advises Mayor Frank Zeidler that "If those colored people want to live that way let them stay down south and don't encourage them to come up here. When they have any money they spend it for whiskey and automobiles."

The Baltimore Sun publishes a letter from Milwaukee resident Frank Evans which reads in part, "The people who live in [slums] make the sleazy houses. Too many of them, I'm afraid, are scared to death of soap and water. They're unclean and slovenly in more ways than one. Their speech is public is also filthy and obscene. Many of them also carry knives and razors, stab and cut each other. ... Why, they even throw their garbage, empty beer cans and whiskey bottles out in the street. The garbage is responsible for the rats. Don't let anybody tell you Milwaukee is the garden spot of Wisconsin. I'm from there -- and I ought to know."

George Ashton, Superintendent, Bureau of Bridges and Public Buildings, writes the following to Mayor Frank Zeidler: "Mr. Alonzo Robinson is an Architectural Designer in our office. He came to us last fall from Wilmington, Delaware and his wife and son [are] still living there because he can find no adequate living quarters in Milwaukee. This young man is a graduate of Howard University and is becoming very valuable to our office. ... Mr. Robinson's problem is so acute because of his race, and it is my hope that your office may provide us with an opening through which we can help Mr. Robinson find a place to rent."

|

1954 | The U.S. Housing Act is expanded to provide for redevelopment, rehabilitation and conservation of the built environment. The law requires that program participants have a "workable program" of urban renewal which includes housing for displaced families.

The Wisconsin Supreme court upholds the constitutionality of the state's Blighted Area Law. Among other things, the statute requires the City Housing Authority to "formulate a feasible method for the temporary relocation of persons living in areas that are designated for clearance and redevelopment" and "assure that decent, safe and sanitary dwellings ... are available, or will be provided, at rents or prices within the financial reach of the income gropus displaced."

City ward plans, establishing a new Second Ward out of parts of the old Sixth Ward, are approved by the Common Council. Vel Phillips announces her candidacy for the Second Ward council seat.

|

1955 | The Milwaukee Commission on Human Rights publishes "The Housing of Negroes in Milwaukee." The report concludes "At the present time, most Negroes must locate within the portions of the city already available to 'nonwhites.' This means that the movement of Negroes and other racial minorities into an area coincides with the withdrawal of white persons out of it. These areas invariable are the oldest and most deteriorated parts of the city... ."

The Milwaukee County Expressway Commission approves a plan for a 40-mile system of expressways, including the North-South and East-West (Park) Expressways.

|

1956 | Vel Phillips is the first woman, and the first African American, to be elected to the Milwaukee Common Council.

The Hillside Terrace Addition is completed.

To meet federal requirements, the common council expands the boundaries of the Hillside Neighborhood Redevelopment Project to include properties on the south side of Walnut Street.

Time Magazine makes note of a years-long "whispering campaign" charging that Mayor Frank Zeidler "has plastered the south with billboards inviting Negroes to Milwaukee, and is therefore responsible for a major migration (actually nonexistent) and a resulting crime wave (Milwaukee has one of the lowest crime rates in the United States)."

|

1957 | The Milwaukee Urban League establishes the 5,000-member Lapham-Garfield Neighborhood Council to combat inequalities facing Milwaukee's African American community.

|

1958 | In February, police shoot Daniel Bell, an unarmed black youth, in the back during a foot chase. Sidney Margoles closes the Regal Theater due to a lack of patronage.

Episcopal Bishop Donald H V. Hallock, a member of Mayor Zeidler's Citizens' Urban Renewal Committee, blasts the Milwaukee County Property Owners Association. "No matter what the civic improvement it was (in the previous seven years) they have been against it," he said.

In a message to the Mayor's Commission on Human Rights, Frank Zeidler calls attention to the difficulties rural migrants encounter, and the negative impact they sometimes have on the community, when they arrive in Milwaukee. He recommends skills training for the newcomers, to ensure they can earn enough to obtain food, fuel and shelter without resorting to criminal activity. He continues, "My office hears many objections to minority groups based on charges that the living habits and standards of some members of these groups are unacceptable to their neighbors. Good structures are broken up, lawns are ruined, garbage and rubbish are strewn around, and perhaps most important, there is no evidence of parental control and discipline over children. ... If the pattern of poor living habits is not overcome by education," he writes, "the neighbors who cannot stand such habits will move away and the beginnings of a ghetto will appear." Zeidler also laments that police officers "are set upon in the course of their duty by people who ... have arrived at the conclusion that the police department is their enemy." Again, the mayor suggests that education is the remedy. "I believe that there is hope for a good educational process which will eliminate incidents of group hostility toward the police officers of the city," he writes.

|

State lawmakers pass the Wisconsin Blight Elimination and Slum Clearance Act, providing for the creation of a Redevelopment Authority in urban areas to oversee redevelopment projects.

| |

1959 | The Upper Third Street Commercial Association publishes "Gold is Where You Mine It," which notes that shopping centers in outlying areas "have had a devastating effect on our 'string street' business areas which were geared to our former street car economy." It further notes that "the three principal stores of Upper Third Street -- Schuster's, Rosenberg's and Bitker-Gerner -- ALL went to Capitol Court. ... The three stores who had built Upper Third Street with their tremendous ability to draw thousands of people here to shop are no longer able to furnish the attraction they once had." The report goes on to recommend a complete make-over to restore the competitiveness of upper Third Street.

|

1960 | Milwaukee's African American population climbs to 62,500.

|

The Mayor's Study Commission on Social Problems in the Inner Core Area of the City issues its "Final Report to the Honorable Frank P. Zeidler, Mayor, City of Milwaukee." The new mayor, Henry Maier, dismisses the report as an "almost indigestible" mass of facts, figures, statistics and bleak reports."

The south side of the African American business district on Walnut Street is demolished as part of the Hillside Neighborhood Redevelopment Project.

The Milwaukee Commission on Human Rights issues its annual report, which includes a review of events from the commission's founding in 1944. The report notes that following World War Two, "there was a greater movement to mechanize agriculture, and this caused the poverty-stricken agricultural worker to attempt to migrate to a city in order to find work. Thus, a migration occurred from the South to all northern cities, of which Milwaukee was one. ... Gradually, older portions of the city, the only areas which would receive the migrants, began to become more densely occupied; and, as the individuals themselves secured work and sought to improve their living conditions, the areas in which they lived naturally began to expand. This tendency to expand was seized upon, unfortunately, by a few persons engaged in real estate transactions. They sought to promote panic in a few areas of this city so that there would be a wholesale selling of homes on the grounds that if the homes were not sold promptly, there would be a drastic loss in value when minority and low-income groups came into the neighborhood." The report also stated that "Concern over an accumulation of incidents in Milwaukee's near Northside, involving street fighting and resistance to police officers' efforts to maintain order, prompted Mayor Frank Zeidler to call a community-wide conference on September 3 [1959], to discuss causes of social problems in the area. Mayor Zeidler indicated that these incidents resulted in a worsening in 'the good feeling' between racial groups." The report noted that 90% of the city's Negroes lived in an area bounded by Holton and Twentieth Streets, and North and Juneau Avenues, a neighborhood characterized by "physical deterioration, excessive traffic, overcrowding of people, littered streets and alleys, lack of adequate play space and green spots, concentration of low-income families, presence of problem and fragmented families, presence of bad forms of recreation, high rates of crime, insecurity of people on the street and group resistance to police in their performance of duties."

| |

1961 | The Plan Commission, Redevelopment Authority and Housing Authority are merged into the Department of City Development.

By fall, right-of-way acquisition is under way for the portion of the North-South Expressway between Keefe and Locust.

Mayor Maier replaces Zeidler's Citizens' Urban Renewal Committee with a new group, the Citizens' Planning and Urban Renewal Committee; 17 of the group's 22 members are city employees.

An article published in the journal Land Economics reveals that the average rate of return on capital investment for 48 slum properties in the Hillside neighborhood is almost 20% per year.

|

1962 | By early 1962, the county has acquired 334 properties along the North-South Expressway route between Keefe and Wisconsin.

Alderwoman Vel Phillips introduces the city's first open housing ordinance. She casts the only "yes" vote.

|

1963 | By the end of the year, the Hillside and Roosevelt Redevelopment Projects have destroyed 264 buildings and displaced 273 families along Walnut Street.

|

1964 | The North-South Expressway is completed between Capitol Drive and Locust Street. Attorney LLoyd Barbee leads a boycott of the Milwaukee Public Schools, demanding an immediate end to racial segregation. According to Barbee, an estimated 15,000 students participated in the boycott, and 11,000 attended one of 33 “Freedom Schools” run in African American church basements.

|

1965 | A research team at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee publishes “The People of the Inner Core -- North.” The North-South Expressway reaches North Avenue. Lloyd Barbee files a lawsuit demanding an integrated public school system.

|

1967 | A violent civil disturbance brings death and destruction to Milwaukee's inner city.

The Milwaukee Journal reports that 90% of the city's Negro population remains confined to the central city, an area bounded by Juneau, Twentieth Street, Keefe and Holton (an area that includes the Hillside and Carver Park public housing projects). It quotes University of Wisconsin Prof. Charles O'Reilly: "Although the area of Negro residence in Milwaukee has expanded into non-blighted parts of the city, the slum remains the home for a large part of the Negro community."

|

1968 | After defeating it six times, the Milwaukee Common Council passes an open housing ordinance that is the equivalent of the recently-passed federal open housing law.

|

1969 | The North-South Expressway (US-141) is completed to the Marquette Interchange. The Park East Expressway opens to 4th St., cutting a swath through the city south of Walnut Street. Acquisition of land and homes for the Park West Expressway is completed. Little consideration is given to relocating those who are evicted.

The Milwaukee Journal quotes Richard W. E. Perrin, the city development commissioner, as reporting that "79% of the 16,544 housing units torn down between 1960-68 [mostly for expressways and other public projects] was without any relocation help to those uprooted."

|

1970 | Milwaukee's black population reaches 105,000.

The Uniform Relocation Assistance and Real Property Acquisition Policies Act mandates that relocation assistance shall be provided in all federal construction projects.

|

1971 | A state court shuts down plans for an elevated expressway along the lakeshore and the state supreme court later affirms in Cobb v. Milwaukee County. The Cobb decision eliminates the rationale for the Park East Expressway and further construction is abandoned.

|

1976 | A federal court judge orders the Milwaukee public school system to end its “consistent and deliberate policy of racial isolation and segregation.”

|

1977 | The expressway-building era in Milwaukee ends with the opening of the Hoan Bridge.

|

1989 | Allis-Chalmers locks the gates to its West Allis plant, which once employed 15,000 people.

|

1990 | The census sets the African American population of Milwaukee at 196,700.

|

1995 | American Family Insurance settles a lawsuit accusing it of race-based insurance redlining (declining to write a homeowner's policy, or imposing more restrictive terms or higher costs, on the basis of a neighborhood's racial or ethnic composition). The U.S. 7th Circuit Court of Appeals wrote, "Lenders require their borrowers to secure property insurance. No insurance, no loan; no loan, no house; lack of insurance thus makes housing unavailable." (The practice precludes loans for renovation as well as for new home purchases).

|

2000 | The black population of Milwaukee reaches 223,000 - 37.3% of all city residents.

|

2007 | Joblessness in Milwaukee among black males age 25-54 is four times higher than the jobless rate among white males (43.2% vs. 10.4%).

|

2012 | According to U.S. Census data, only 36% of working-age males and 50% of females have jobs in the predominantly Africa American 53206 zip code, compared to 67-68% in the city as a whole. Virtually all of those in the who work have jobs outside of the zip code; many have commutes that are longer than 45 minutes. The poverty rate in zip code 53206 is 48%, compared to 28% in the city. With the exception of educational attainment, most social indicators in zip code 53206 declined between 2000 and 2012.

|

Documentary Resources

Arts, Enterainment and Recreation

- An Improvised World: Jazz and Community in Milwaukee, 1950-1970

- Blues, Bebop and Bulldozers: Why Milwaukee Never Became a Motown

Civic Leaders

- Carl F. and Frank P. Zeidler Papers 1918-1981, Milwaukee Public Library

- Governing the Regimeless City The Frank Zeidler Administration in Milwaukee, 1948–1960

- Records of Mayor Henry W. Maier Administration, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 1957-1989, UWM Libraries Archives

- Some Conditions in Milwaukee at the Time of Brown v. Board of Education (Zeidler)

- The First Mayor of Black Milwaukee: J. Anthony Josey

Demographics

- Black Milwaukee, Proletarianization, and the Making of Black Working-Class History

- Milwaukee's Negro Community 1946

- The Development of an Urban Subsystem: The Case of the Negro Ghetto

- The Incidence and Ecological Pattern of the Ten Leading Causes of Death for the City of Milwaukee in 1941

- The Inner Core North: A Study of Milwaukee's Negro Community (Zeidler Report)

- The People of the Inner Core North: A Study of Milwaukee's Negro Community

- The Reluctant City: Milwaukee's Fragmented Metropolis, 1920-1960

Economics and Employment

- From Walnut Street to No Street: Milwaukee's Afro-American Businesses, 1945-1967

- Looking Beyond the Numbers: The Struggles of Black Businesses to Survive: A Qualitative Approach

- Negro Business Directory, 1950

- Race, Jobs, and the War: The FEPC in the Midwest: 1941-46

- When Work Disappears

- A Dream Derailed (Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

Education

- African Americans' Continuing Struggle for Quality Education in Milwaukee, Wiscsonsin

- The Impact of School Desegregation in Milwaukee Public Schools on Quality Education for Minorities

- The Impact of the Milwaukee Public School System's Desegregation Plan on Black Students and the Black Community (1976-1982) (Fuller)

Housing

- The First Public Housing: Sewer Socialism's First Garden City for Milwaukee

- The Housing of Negroes in Milwaukee: 1955

- Preservation and the Projects: An Analysis of the Revitalization of Public Housing in Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Police, Crime and the Courts

- Cocaine, Kicks, and Strain: Patterns of Substance Use in Milwaukee Gangs

- Gangs, Neighborhoods and Public Policy

- Kids, Cops and Beboppers: Milwaukee's Post-WWII Battle with Juvenile Delinquency

- Occupied Territory: Police Repression and Black Resistance in Postwar Milwaukee, 1950–1968

Race Relations and Civil Rights

- A Report on Past Discrimination Against African Americans in Milwaukee, 1835-1999

- Attitude Study Among Negro and White Residents in the Milwaukee Negro Residential Areas

- Four Decades Later, Poverty Persists: Where Riots Raged, Signs of Poverty, Decay (Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel)

- From Socialism to Racism: The Politics of Class and Identity in Postwar Milwaukee

- Future Political Actors: The Milwaukee NAACP Youth Council's Early Fight for Identity

- Polish American Reactions to Civil Rights in Milwaukee

- Summer Mockery (1967 Uprising)

- The Milwaukee Press' Treatment of Father James E. Groppi at the Height of the Open Housing Demonstrations

- The Negro in Milwaukee (1942)

- The Selma of the North: Race Relations and Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee, 1958-1970

Religion

- African-American Catholicism in Milwaukee: St. Benedict the Moor Church and School

- African American Socialization in Milwaukee: The Role of the Catholic Church

- A History of the Ministry to African American Catholics in Milwaukee, 1908-1963

Transportation

- Mayor Frank P. Zeidler: transportation development in post-war Milwaukee, Milwaukee Public Library

- Through Highways: Construction of the Expressway System in Milwaukee County, 1946-1977

- Relocation of Families Displaced by Expressway Development: Milwaukee Case Study

Urban Renewal

- The Blight Within Us (Milwaukee Journal special report, May 1954)

- The Unworkable Program: Urban Renewal in Kilbourntown-3 and Midtown, Milwaukee

- Urban Renewal and the Development of Milwaukee's African American Community: 1960-1980

- Bronzeville Blog

- City of Milwaukee Online Data Resources

- Milwaukee's Black Heritage

- Milwaukee Renaissance

- Old Milwaukee

- Recollections Wisconsin

- Retro Milwaukee

- Urban Anthropology

- Milwaukee County Historical Society

- Milwaukee Courier

- Milwaukee Jewish Historical Society

- Milwaukee Police Department

- Milwaukee Public Library Historic Photograph Collection

- Negro Business Directory

- St. Benedict the Moor Church

- University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries Archives

- Wisconsin Black Historical Society/Museum

- Wisconsin State Historical Society